[ad_1]

Aaron KileyCar and Driver

Read more from Car and Driver‘s Greatest of All Time package, which appears in July’s issue.

There’s an easy case to be made that we are living in the car’s greatest moment. Time passes; technology advances. Unless your DeLorean has a functioning flux capacitor, you’ll be hard-pressed to find a more sophisticated vehicle than what’s on dealer lots today.

These are the muscle car’s glory days, with creatine-snorting monsters that corner as hard as they accelerate. The most efficient car ever sold, the Tesla Model 3 Standard Range Plus, clears 60 mph in a claimed 5.3 seconds. Two-and-a-half-ton luxury SUVs can turn credible lap times. Mid-engine cars practically grow on trees. No matter your budget, you have more choice than ever in what you drive.

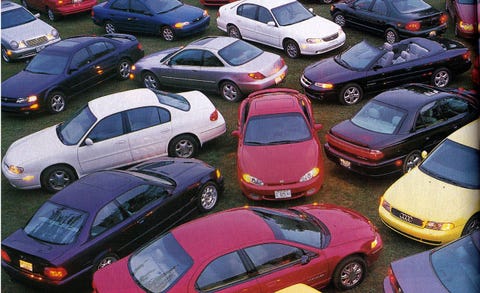

But assuming you’re not on Ferrari’s short list to buy a $625,000 SF90 Stradale, the greatest time to be a car enthusiast has passed. That era began in the mid-’90s, when technology and business philosophies and the political climate aligned, and lasted through the mid-2000s. It produced a glut of sports cars, exotics, performance compacts, and hot-rod sedans with palpable and distinct character. We may never experience the breadth and depth of such great cars again.

The in-house tuners were run by engineers then, not MBAs, and they understood that their cars were special because of what was under the hood and how they drove, not what badge was on the trunklid. Automakers tooled up assembly lines to build unique powertrains—from cylinder heads to tailpipes—and to install bespoke chassis components for a single low-volume model. They built engines with lofty redlines, ramplike power curves, and soulful exhaust notes to give the engines as much personality as performance. Turbochargers were used sparingly and purposefully in cars like the WRX and Evo, where a late wallop of boost was a part of the car’s rally-inspired costume.

In 2020, Ford’s Mustang Shelby GT350 is among the last cars to channel that past. It uses exclusive purpose-built hardware where it matters—namely the howling 8250-rpm V-8—and mass-production parts where it doesn’t. But the GT350 does fall victim to the other force that’s smudging performance cars into homogeneity: excess. With thrust by Pratt & Whitney and tires by Gorilla Glue, today’s performance cars are measured on a time scale that the human brain can barely keep up with. What’s the difference between 600 and 700 horsepower? When cars are this quick, we might as well be comparing a sneeze and the blink of an eye.

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, cars still moved at speeds that humans could comprehend. Performance matched the roads we drove on. Horsepower was in abundant supply, but the quick cars were rarely so heady that drivers needed the crutch of all-wheel drive or an automatic transmission to wrangle their full potential. No one talked about shift speeds because enthusiasts drove manual transmissions. And the cars they drove flooded their senses without overwhelming them. They were analog and emotional, unfiltered and pure. Today’s most powerful and quickest and grippiest will inevitably be dethroned by the march of progress. The heroes of the ’90s and early aughts achieved greatness through a mix of attributes that gets rarer by the day.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

This commenting section is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page. You may be able to find more information on their web site.

[ad_2]

Source link