[ad_1]

Professional racer John Paul Jr. died Tuesday at 60, after a long battle with Huntington’s disease. This profile of his life and his complex relationship with his father, John Paul Sr., originally appeared in the November 1997 issue of Car and Driver.

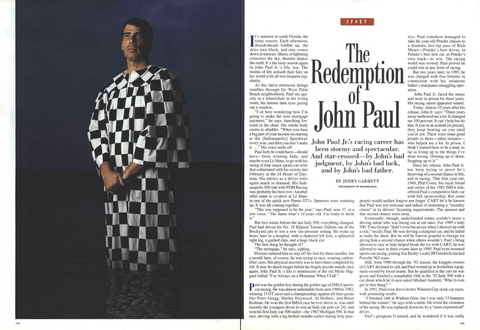

The Redemption of John Paul Jr.

It’s summer in South Florida, the rainy season. Each afternoon, thunderheads bubble up, the skies turn black, and rain comes down in torrents. Sheets of lightning crisscross the sky, thunder shakes the earth. It’s the rainy season again in John Paul Jr.’ s life, too. The storms of life unleash their fury on his world with all-too-frequent regularity.

As this latest afternoon deluge rumbles through his West Palm Beach neighborhood, Paul sits quietly in a wheelchair in his living room, his intense dark eyes gazing out a window.

“I sit here wondering how I’m going to make the next mortgage payment,” he says, hunching forward in the chair. His whole body seems to shudder. “When you base a big part of your income on running at the [Indianapolis] Speedway every year, and then you don’t make it . . . ” His voice trails off.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Paul feels he could have—should have—been winning Indy, and maybe even Le Mans, to go with his string of four major sports-car wins that culminated with his victory last February at the 24 Hours of Daytona. His talents as a driver were again much in demand. His Indianapolis 500 ride with PDM Racing was probably his best ever. Another offer came to co-drive at Le Mans in one of the quick new Panoz GTls. Sponsors were warming up. It was all coming together.

”This was supposed to be the year,” says Paul, now 37, in a low voice. ”The damn wine’s 10 years old. I’m ready to drink it.”

But two weeks before the last Indy 500, everything changed. Paul had driven his No. 18 Klipsch Tnemec Dallara out of the Brickyard pits to test a new tire-pressure setting. He woke up hours later in a hospital with a shattered left foot, a splintered right leg, a gashed chin, and a huge black eye.

The first thing he thought of?

”The mortgage,” he says, sighing.

Doctors ordered him to stay off his feet for three months, but a month later, of course, he was trying to race, wearing carbon-fiber casts. His physical recovery was to have been completed by fall. It may be much longer before his fragile psyche mends once again. John Paul Jr.’s life is reminiscent of the old Merle Haggard ballad “I’m Always on a Mountain When I Fall.”

Paul was the golden boy during the golden age of IMSA sports-car racing. He was almost unbeatable from mid-1980 to 1982, winning 13 GT races and a championship, against all-time greats like Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, Al Holbert, and Brian Redman. He won the first IMSA race be ever drove in, was until recently the youngest driver to win an IndyCar pole (at 24), and won his first IndyCar 500-miler—the 1983 Michigan 500. In that race, driving with a leg broken months earlier during Indy practice, Paul somehow managed to take his year-old Penske chassis to a dramatic last-lap pass of Rick Mears—Penske’s best driver, in Penske’s best new car, at Penske’s own track—to win. The racing world was wowed. Paul proved he could win in any form of racing.

But two years later, in 1985, be was charged with five felonies in connection with his infamous father’s marijuana-smuggling operation. John Paul Jr. faced the music and went to prison for three years. His racing career appeared ruined.

Today, almost 10 years after his release, John Jr. says: ”Three years away mellowed me a lot. It changed me 100 percent. It can’t help but do that. If you’re an asshole [in prison], they keep beating on you until you’re not. There were some good people in there—other inmates—who helped me a lot. In prison, I think I learned how to be a man, as far as living up to the things I’ve done wrong. Owning up to them. Stepping up to it.”

Since his release, John Paul Jr. has been trying to prove he’s deserving of a second chance in life, and in racing. That first year out, 1988, Phil Conte, his loyal friend and owner of his 1985 IMSA ride, offered Paul a competitive Indy car with full sponsorship. But some people would neither forgive nor forget. CART let it be known that Paul was not welcome and talked of instituting a “morality clause” in its drivers’ licensing requirements. The sponsor and that second chance went

Eventually, though, underfunded teams couldn’t resist a driving talent who was hiring out at cut rates. For 1989’s Indy 500, Tony George “didn’t even bat an eye when I showed up with a ride,” recalls Paul. He was driving a marginal car, and he failed to make the show. But he will be forever grateful to George for giving him a second chance when others wouldn’t. Paul’s being allowed to race at Indy helped break the ice with CART; he was allowed to race in three events later in 1989. Paul even resumed sports-car racing, joining Jim Busby’s solid BFGoodrich-backed Porsche 962 team.

”This was supposed to be the year. The damn wine’s 10 years old. I’m ready to drink it.”

Still, from 1990 through the ’92 season, the kingpin owners of CART declined to call, and Paul wound up in borderline equipment owned by lesser teams. But he qualified in the cars he was given and finished a remarkable 10th in the ’92 Indy 500 with a car about which he’d once asked Michael Andretti, “Who’d even get in that thing?”

In 1991, Paul even drove in two Winston Cup stock-car races, with promising results.

“I finished 14th at Watkins Glen, but I was only 13 bumpers behind the winner,” he says with a smile. He loved the closeness of the racing. He was replaced, however, by a “more experienced” driver.

Paul’s prospects U-turned, and he wondered if it was really only a matter of “experience,” or sponsor acceptance. He had no regular rides in 1993 and ’94. By ’95, he was virtually ignored at Indy. “I stood there the whole week before qualifying—the first time I’d gone to Indy without a ride—and never got offered a thing,” he recalls, wincing at the memory. “I figured it was the end of the line. Then [IMSA car owner] Rob Dyson called and offered me a road-racing ride that paid prize money plus a salary. I took it—I got out of Dodge.”

He got a big break in 1996 with the creation of the Indy Racing League. Paul Diatlovich and Chuck Buckman formed a team and then cajoled John Menard into giving them a tired Buick V-6 from his show car. They hired Paul to race for prize money. Battling engine reliability, Paul had an impressive season; he even led at Las Vegas and finished 15th in the points standings.

“Everyone who was involved in Indycar racing when I was indicted, and for the time I was gone, they have long memories,” Paul says wearily. “They haven’t forgotten about it. The ones who have been around forever still haven’t put it behind them. And I can understand that.”

Car and Driver

But the situation is improving, and the Richard Nixon scowl on his face gives way to his leading-man smile when he continues, “Luckily, there are enough sponsors who have come in new and who see me at face value. For the most part, they haven’t been huge companies. But it has slowly been getting better. I have to keep in perspective that even drivers like Arie Luyendyk struggle to find sponsors. It’s not just me.”

Today, he does volunteer work with drug-abuse clinics. His derailed personal life is also back on track. He and his wife, Patricia, had been separated for two years but are back together. “We beat the odds—90 percent of all marriages fail when you go to prison. She met me after the smuggling had stopped. But she’s had to endure everything that’s happened because of it. I feel terrible about what she’s been put through.”

At home again with Patricia and their children, Alexandra, 13, and Jonathan, 4, Paul feels a strong need for family.

“My mother died in November,” he says, struggling to retain composure. “She was sick for a long time, so I had time to come to terms with it. But it’s still hard to deal with. I have a lot in my makeup that is my mother, versus my dad. The easy-going side. That’s her stuff. She was always happy about my racing career. Although she couldn’t go to races, she watched on TV. When she died, I thought she was up there, looking out for me. I was starting to win races again.”

Then came that unthinkable crash last May 9 at Indy, on the eve of his first Mother’s Day alone. “I have no idea what happened, and that bothers the hell out of me. I hit my head on the side of the tub, and I can’t remember any of it.”

At six foot four, he’s especially vulnerable in any crash. “It’s not that you think you’re invulnerable. You just don’t think it’s gonna be you who crashes. We had put 1100 miles of testing on the car. I had confidence. I was in the zone. “

Other teams were in awe of how fast Paul was running. He finally seemed to have regained the speed he says he lost while in prison. If he was that fast in practice, he’d be the one to beat in the race.

His fellow drivers were relieved that Paul turned out to be a problem they didn’t have to deal with. Their respect for him was shown when they later honored him with the inaugural Scott Brayton Award for his “competitiveness, desire, and spirit.”

If Mother’s Day is an emotional stemwinder for him, Father’s Day is an equally mixed bag. It was John Paul Sr. who was the catalyst for his son’s remarkable racing career. It was also Paul Sr. who got his son into crime—and failed him miserably.

“I resent what my father did,” says Paul. “He’s a very intelligent man and could have done things differently. But I know he feels bad about it.”

Indeed, in 1988, the elder Paul wrote his trial judge: “The humiliation and the bad publicity I caused my family . . . caused me to be so depressed I continually considered suicide as the only answer to my problems . . . I am truly sorry, and I am sure in my heart I will never have anything to do with drugs in the future.”

Right now, John Paul Sr. is in a federal prison in Jesup, Georgia. Under our unique judicial system, Paul Sr., with time off for good behavior, will serve 14 years of a 25-year prison sentence for drug trafficking and passport and income-tax fraud. He is scheduled to be released sometime after December 1998. He was actually eligible for parole four years ago, but the federal government declined to let him go.

The two Pauls speak regularly to each other, even though Senior can make only collect phone calls. Getting together in person is sometimes difficult, since Senior is moved often from prison to prison, a routine practice to keep certain inmates from “establishing contacts” and possibly collaborating with other prisoners who might have “similar interests.”

His son does not believe that Paul Sr. might return to racing after his release. “I know he won’t be around racing anymore.”

How much the father will be around his son after his release is less clear. “JohnJohn,” as his father still calls him, is still sorting out his mixed feelings on that subject.

“My dad was the hardest guy to live with,” Paul explains in measured tones. “It was very hard for him to understand that someone wasn’t as smart as he. He’d want things done in a certain way, and he expected them to be done that way. He couldn’t understand if people didn’t see that’s how it should be done. And a lot of times, it didn’t matter how you would have done it. It would have been wrong.” He sighs, then adds, “I try not to be that way with my own son.” John Jr. criticizes himself for “yelling at” his wife too often, and for losing his temper, “usually about little things.” He knows where this behavior comes from.

His father, John L. Paul, emigrated with his parents—his father was a medical radiologist—from Holland to Muncie, Indiana, in the mid-1950s. Just 15, John Paul was full of promise, gifted in mathematics. But the trouble he initially had learning English, coupled with a quick temper, kept him from fitting in; he was thrown out of three high schools before graduating.

“My dad was 20 when I was born. My mom was 16. They ran away together,” Junior explains. “At that time, my father had a job his father had gotten him, washing dishes in Ball Hospital in Muncie. He decided he finally had to get his act together. He graduated from Ball State and applied for a fellowship to the business school at Harvard, and was accepted.” He moved his family—his wife, Joyce, two-year-old John Jr., and year-old Tonya—to Massachusetts. Another son, Michael, was born there. They stayed eight years.

On graduation from Harvard, John Sr. signed on with Putnam Management, a Boston mutual-fund firm. There, he became a legend; he was quickly promoted to co–fund manager, and the fund grew from $600 million to $4 billion in six years. Before his 30th birthday, he was a millionaire.

Paul Sr. invested in burgeoning companies like Mattel Toys and Kentucky Fried Chicken. Mattel later gave Paul Sr. a plaque inscribed, ”Without John Paul, Mattel would have never made it.” His son, who has kept the plaque, can hardly speak of it without tears welling up.

On the other hand, he’s able to look back at that time and criticize his father’s choices, lamenting that his dad had an uncanny ability to make money illegitimately.

It was the Sixties, the drug culture was in full bloom, and marijuana use was widespread, accepted. One day, Junior was asked to take his siblings to a nearby playground. “But I came back early. My dad had some friends over. They were all in there smokin’. That was the first time I’d ever seen it. I was nine years old. Dad sat me down and said, ‘Your mother doesn’t agree with this, but I don’t see how it’s harmful.’ “

His father welcomed outlets from his pressure-packed life in high finance. “As part of his signing bonus with the firm, my old man got a brand-new ’64 Corvette. He drove past an autocross in a mall parking lot and decided to try it. That’s how he started racing. Later, he bought a street Cobra.”

By 1970, Paul Sr. had bought Sam Posey’s old Trans-Am Dodge Challenger and started winning races in Connecticut at Lime Rock, Bridgehampton, and Thompson.

But racing proved to be a two-edged sword for the family. “My mother started to date another race-car driver,” John Jr. says, now staring blankly ahead. “That was a bad time. There was a lot of yelling and screaming in the house. My parents split up. My mother moved back to Indiana. I went with her. I was 10. We lived in a house trailer for three years. We bought our groceries with food stamps.”

Although no angel himself, Paul Sr. was devastated by his wife’s affair. He quit his job, sold everything he owned, bought a sailboat, and sailed away. Two years later, on John’s 12th birthday, a deeply tanned, bearded pirate appeared at their trailer in Muncie. It was his father.

“He came back to see me,” John Jr. recalls emotionally. “After that, he used to come visit me sometimes. He’d show up in the middle of the night.”

John Sr. and Joyce eventually decided to try again. The family moved to Dad’s new waterfront home in Florida. The reunion was rocky. The yelling and fighting continued. His parents separated four times, finally divorcing. Joyce wouldn’t live with a drug smuggler.

“I wanted to be involved with my dad. I just wanted to be with him.”

John Jr. recalls how the dope smuggling began. His father’s two-year odyssey had ended in Florida. He met some people there who said: “You have this sailboat. Why don’t we make some money with it?’ So he sailed to west Jamaica . . . “

In the mid-Seventies, drug smuggling in Florida had reached comical proportions. The sky was raining marijuana bales; the beaches were awash in waterproof plastic bundles. One day, John Jr. opened the family’s garage and found it piled high with bales of marijuana. He confronted his father.

His father, a fervent believer in his right to smoke marijuana and an advocate for its decriminalization, said, “Well, what do you think?”

John Jr. recalls, “I didn’t know what to think.”

His father recruited him to help unload. At the time, it occurred to John Jr. this might be dangerous and illegal, not to mention downright dumb, but the opportunity to do something—anything—with his father was overpowering. “I wanted to be involved with my dad,” he recalls. “I just wanted to be with him.”

So together they sailed the East Coast and offshore islands. Over the Christmas holidays in 1976, they drove to Kansas to pick up a Porsche Carrera that his father had purchased for racing. It was “a good time” for father and son.

Those good times were interrupted in the fall of ’77 when John Jr. had to return to Muncie for his final year of high school. He hated it: “I never was any good in school. I just put in my time.” When he graduated, his life was at a crossroads. “Well, if I had stayed living with my mom, probably nothing would have happened. I would have been pumping gas, or working in a Goodyear tire store, something like that.”

Life in Muncie was dull. Nothing to do. Nowhere to go. Trailer parks. Food stamps. Paul Sr. had been sending Joyce $300 a month, but after the divorce, he cut them off.

John Jr. decided to return to his dad and the good life. He even began smoking marijuana, just like his father. He was captivated by his fearless father—wanted to know him better, wanted acceptance and approval.

Paul Sr., with his imperious manner and fiery temper, was a strong role model and male authority figure. His father was also a hopeless perfectionist. The people who worked for him—John Jr. included—endured constant verbal abuse.

“I think he was so much of a perfectionist himself, and had such high expectations, he felt everyone else should be the same way,” says John Jr.

But at least John Jr. felt like he belonged. He had an important assignment, helping to unload the marijuana boats and then trucking the contraband to safe storage locations.

It was harrowing work. After nearly being caught in March 1978, father and son were nabbed in January 1979 as they and an accomplice, Chris Schill, were unloading the last of a 20-ton shipment in a Louisiana bayou. But since they were caught with only 1500 pounds (the bulk had been dispersed) and had no police records, the three men, in exchange for guilty pleas to marijuana possession with intent to distribute, received suspended three-year prison terms and three years’ probation, and paid six-figure fines and forfeitures.

After this debacle, Paul Sr. decided his son needed to go to driver’s school. “My old man didn’t send me to learn how to be a race driver,” John Jr. remembers. “He sent me to improve my driving on the street. I had an accident the first week I got my license. On the highway, I was a really bad driver. It was funny, because when I went to the Skip Barber school, I went with my father’s girlfriend at the time. My father showed up on the last day and asked the instructor, ‘Well, how’d they do?’ The instructor said to him, ‘Well, she’s pretty good—but the kid, he’s hopeless!”‘

In spite of that, his father bought him an old Formula Ford. And, thus, Junior’s racing career began, and quickly blossomed. Cash to build or buy race cars never seemed to a be problem, although John Jr. is adamant that JLP Racing never spent as much money as people thought, or as much as competitors did. Yet the Pauls seemed to come out of nowhere to win races and IMSA and SCCA championships.

Just before the race season got under way in January 1981, with a year left on their probation, Paul Sr. and Jr. went with several other men to Louisiana to unload their biggest shipment ever, 40 tons of marijuana. Two tractor-trailers loaded and left, but a third truck was reported to police, who arrested its drivers. The boat that was being unloaded was piloted away, but it couldn’t escape because a nearby railroad drawbridge had been lowered, trapping them in the area. Three smugglers onboard jumped off and were fished out of a chilly bayou nearby as they tried to swim away. The Pauls and two accomplices were also in the area but eluded police.

Later, Paul Sr. bailed out the five jailed men and paid a $500,000 fine in cash.

This fiasco was sufficiently frightening that Paul Sr. quit smuggling. In six major shipments from 1975 to 1981, Paul Sr. had allegedly smuggled more than 100 tons of Colombian marijuana into the U.S., with the help of his partner, David Cassorla, Stephen Carson, and other accomplices. That much marijuana, according to smugglers, was probably worth $40 million. The Drug Enforcement Administration, which often announces the highest-possible street value of seized drugs, estimates $225 million.

”They were apparently buying the stuff for 50 cents or a dollar a pound and then turning around and selling it—depending on the quality—for up to $1000 a pound, wholesale,” says a DEA source. “When you see the enormous profit potential, you begin to understand how hard our job is. We are dealing with some very motivated individuals.”

John Sr. retired from racing in 1982. He married Hurley Haywood’s sister, Hope, and they soon had a daughter, Adrienne. He had stopped smuggling, but he didn’t get out of the marijuana business. Instead, he bought a 596-acre farm outside Atlanta in December 1982 and then spent something like $500,000 trying to construct a gargantuan underground marijuana-growing operation, lit by thousands of “grow lights” and powered by a massive generator. Theoretically, it was a sound business decision since hydroponically grown marijuana can be worth roughly twice as much as field-grown pot. He hoped to harvest three or four crops a year.

Early in 1983, Chris Schill was subpoenaed to appear before a federal grand jury investigating drug smuggling. He simply disappeared. Five Florida men linked to Cassorla were indicted; more indictments were expected. Stephen Carson decided to cooperate with a grand jury in return for immunity.

Enraged, Paul Sr. caught up with Carson late one night on a pier in Saint Augustine, Florida, and shot him five times with a .38-caliber pistol. Somehow, Carson survived. Then, after allegedly trying to buy silence from two other federal witnesses, Paul Sr. dropped out of sight for weeks. He later surrendered to Florida authorities, who charged him with attempted murder.

When the story broke in April 1983, Paul Sr. became the butt of jokes—mostly about his poor marksmanship. For years, rumors among fellow racers had abounded about Paul’s smuggling, yet no one had been willing to go on record. The “simpatico” racing press had seemed to go out of its way to avoid the story. Now, it was open season. Senior jumped bond in late 1983, and disappeared for more than two years.

Junior, meanwhile, had an agonizing decision to make: flee with his father, or stay and try to make a life on his own in racing. His father made it easy for him to run, providing him with a fake identity and matching passport.

“That’s where we see things differently,” John Jr. says today. “Even with a traffic ticket, I stop and pull over. I don’t run. I just take what’s coming. I guess that’s my mother’s influence.” Junior thinks his father’s flight from prosecution was a stupid move. “It didn’t seem like the way I wanted to live the rest of my life. I was living on borrowed time. It wasn’t fun. But there was nothing I could do about it. I just had to live day by day and accept what happened, when it happened.”

John Paul Jr. was truly on his own. To survive, he picked up rides on a race-by-race basis. He snagged a top-flight IndyCar ride for 1985, but he was indicted three days after signing and had to resign. He was replaced by Al Unser Jr., who went on to finish second by one point to his dad, Al Sr., for the IndyCar championship. Now, there’s a contrast in father-and-son dynamics.

John Jr. still had a chance to rescue his career and avoid jail time. The most damning pieces of evidence against him: a false passport, which he had used once to go to Canada to help his father’s wife, Hope, sneak back into the U.S. and twice to visit his fugitive father in the Bahamas, and the Louisiana parole violations in 1981. “If I had testified, or told them I would have testified against my dad, I probably could have gotten out of it,” he says. “But I never even let the attorneys pursue it. They were gonna find me guilty of something. There was no doubt. Or there would have been a probation thing.”

Junior professes no regrets about not testifying. “He was my dad,” he says.

So John Paul Jr., internationally renowned racing driver, pleaded guilty to racketeering and passport fraud and was sentenced to five years; he would serve almost three. Just as John Jr. set off to begin serving his sentence in a minimumsecurity prison in Alabama, his father was being extradited from Switzerland, where he had been caught. Paul Sr. faced life imprisonment without parole for heading a “continuing criminal enterprise” and committing 12 other felonies.

In plea bargaining, his lawyer, Ed Garland, got the charges reduced to a “catchall” racketeering charge, plus passport and IRS fraud, in exchange for a guilty plea. Carson, meanwhile, won a $50,000 civil judgment against Paul and then disappeared into the federal witness-protection program.

Two accomplices also went to jail. Chris Schill evaded capture until 1988, and got 10 years. He complained that he did no more than John Jr. had. Three others who had been indicted, including Paul’s partner, Cassorla, have never been captured, and the case remains open.

As the prison doors slammed shut on the Pauls, other top drivers in IMSA were also in trouble with the law. Several went to prison for drug-related offenses. The sport got a black eye, from which it arguably never recovered.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

“I hurt the sport a lot,” John Jr. acknowledges. “I hate what I’ve done. It’s hard to live with it. But I’ve made a point of trying to be as honest about it as I possibly could. I didn’t see there was any other way to be able to drive again. I had to be accountable—whether it hurt me as far as finding rides or not.”

In hindsight, what could he have done differently?

“I could have told my dad no.”

No flak or hassle for you?

“No.”

So, you went in knowing full well the consequences of your actions?

“Well, you know you could go to jail, but it didn’t seem like a reality.”

Sort of the way racers think about the possibility of crashing?

“It’s like thinking your house will never be robbed.”

What was your rationale for continuing as you got older, especially when you weren’t making any money at it?

“It was being with my dad.”

[ad_2]

Source link