[ad_1]

UPDATE, 2/19/2021: Bruce Meyers, creator of the Meyers Manx dune buggy, has passed away at age 94. Meyers had recently sold his company, which he founded in 1964. During his long life, Meyers brought a lot of joy to the world and helped launch at least one auto journalist’s career. And the Manx, like its creator, was a joyful car, leaving behind a wake of smiling passersby wherever it was driven. —Rich Ceppos

I felt a warm rush of nostalgia when I learned that Bruce Meyers, the 94-year-old creator of the Meyers Manx dune buggy, sold his company. Way, way back in the day, I built a Manx. It did not go smoothly. It did not end well. But for a college kid whose automotive skill set consisted solely of knowing how to create massive clouds of tire smoke with his mother’s Pontiac GTO, building something that passed for a car—even one that broke down all the time—turned out to be a gift.

I did not set out to build a Manx; it was a matter of expedience. The summer after my freshman year I was mesmerized by a used TVR, a spunky British sports car guaranteed to spend virtually all of its time in the repair shop. My parents recoiled and refused to front me any money towards it, and I didn’t have enough to buy it on my own.

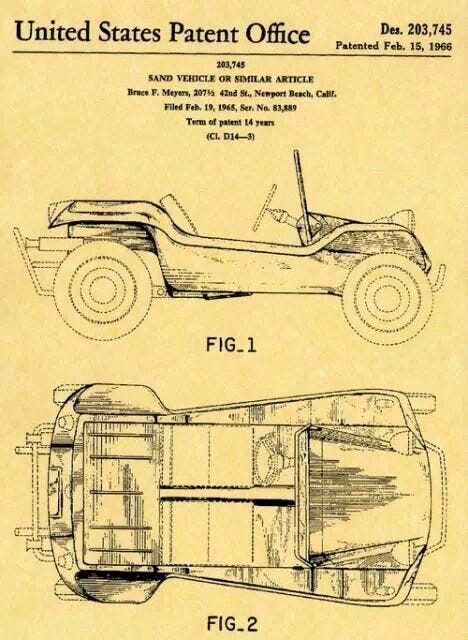

So I hatched a scheme: I’d spend the summer—when I wasn’t working in my neighbor’s factory, processing faux-fur pelts—building my own “sports car.” I’d seen stories about the Manx. In my fevered imaginings, a featherweight fiberglass bathtub of a body plopped atop a Volkswagen Beetle chassis and powered by a hopped-up VW flat-four engine sounded perfect. After all, early Porsches were just hot-rodded Beetles. My Porsche would just happen to look like a beach buggy.

My plan was to enter the Manx in local autocrosses and demoralize the nerdy sports car set by blowing the wire wheels off their wimpy MGs and Triumphs. Eat Manx dust, you weenies! Mom and Dad liked the idea of knowing where their long-haired hippie kid would be all summer: out of trouble, struggling in the garage to build some cockamamie car. They released the funds.

I purchased the gold metalflake Manx body and associated components from a guy selling all the required hardware out of the back of a paint store. I picked up an engine-less Beetle donor car that had been in a rollover accident and the VW flat-four engine from a junkyard. And then, with absolutely no mechanical skills or experience whatsoever, but with a copy of Chilton’s Volkswagen Beetle Repair Manual in hand, I dove into the project.

Courtesy Meyers Manx

The neighbors must have loved when I unbolted the Beetle body from the floor pan. It comes off after unfastening 32 bolts. The fenders, bumpers, and doors come off with it. With the help of my father I flipped the body off the chassis and on to its side. For two weeks it languished in our driveway. Visitors driving up the street of our suburban Long Island neighborhood must have thought there’d been a rollover accident pulling into our garage.

I bought a ratchet set and tore into the junked engine, blissfully unaware that it had suffered a catastrophic failure that melted the connecting rods to the crankshaft. No worries. I’d build it back better than ever. Forget that I’d never so much as touched a wrench to an engine before. One advantage of being young and dumb is not knowing what you can’t do. With help from a local machine shop, and my best friend’s father (who restored classic cars in his spare time), I got it reassembled. Except for a couple of extra parts that would later prove critical.

I labored past midnight every evening, and by late summer was barely able to stay awake at work. But I had the gleaming body bolted to the Beetle chassis, the engine in, and the original Beetle wiring harness reinstalled—incorrectly. When I tested the turn signals, the right headlight blinked along with the left rear brake light. And when I fired the engine—to my amazement it coughed to life—I burned out the starter motor because I’d crossed the wires on the ignition switch. Who cared? I had built a running car.

Courtesy of Meyers Manx

Well, sort of. Once the Manx was mostly finished and on the road, the next 12 months revealed the Grand Canyon-sized chasms in my mechanical aptitude. Henry Ford once said, however awkwardly, “Failure is only the opportunity more intelligently to begin again.” The Manx was one opportunity after another.

Right off, there was something wrong with the engine, which was emanating an ominous pffft-pfftt-pfftt after less than 100 miles. The mechanic at the corner service station was kind enough to enlighten me that the cylinder heads were about to fall off; I’d failed to re-torque them after running-in the new engine.

With the heads retightened, the motor was still way down on power. Despite its displacement now being about 30 larger than stock, its hotter cam, and its blaring free-flow exhaust, the Manx wouldn’t go any faster than a stock 40-hp Beetle. No one told me the standard single-barrel carburetor would be too small to feed the newly enlarged engine.

I did know this: I was feeling cool in my gold metalflake sports-car buggy-thing. People stared. I acted nonchalant, all the while hoping the Manx wouldn’t blow up as I passed. I left it at home for the fall semester; I would show off my handiwork on campus in the spring. I pictured myself arriving at anti-war rallies, the only dude in a growling dune buggy. Maybe the other protesters would think I’d just rolled in from the West Coast to help my Massachusetts brothers and sisters stick it to the man.

But there was reality to deal with first. This desire to get the Manx up to school as early in the spring as possible led to the Greasy Underwear Incident. The 160-mile trip to Amherst, Massachusetts on a cold and rainy March day turned ugly 50 miles in as the Manx sputtered to a stop on the side of I-95 in Connecticut. I peered into the carburetor: was that ice? So that’s what happens when you fail to hook up the carburetor pre-heater tube.

Brilliantly deducing that the intake system needed insulation to keep it warm and prevent further icing, I knew what I needed to do: I reached into the duffel bag of clothes my mom had just washed for me, pulled out a dozen pair of undershorts—all of them white, no less—and stuffed them around the oily intake manifold and carb. The Manx restarted, ran for a half-hour and crapped out again. And it kept on dying at ever-shorter intervals as I drove north and the temperature dropped. The normally three-hour trip had stretched to nine when I abandoned the Manx at a gas station 20 miles from school and called my roommate to pick me up. And yes, I sported grease-stained undershorts for the rest of the year. It was a look.

More memorable mechanical lapses punctuated the remainder of the school year. The throttle cable fell off and the car had to be nursed back to campus using a long string to operate the throttle by hand. The brakes failed as I was approaching a toll booth; good thing I’d just repaired the emergency-brake cable. Despite its convertible top and side curtains, rain poured into the interior and sloshed around on the floor. Thanks to a broken clutch cable, I was forced to make the entire trip home at the end of spring semester shifting without the clutch. Getting away from stoplights involved lots of embarrassing lurching.

I never did make it to an autocross, but the summer after I built it I decided to use the Manx like the dune buggy it was and snuck into a local sand-and-gravel pit. The engine didn’t run too well after that; the oil was gritty. I hadn’t been able to figure out how to fit an air cleaner into the tight space in the engine bay, so I assumed sand wouldn’t get in there either. Wrong again.

I rebuilt the engine a second time and left the Manx home in the fall. Back for winter break I decided to start it up just to hear it run. The Manx had one last lesson for me. Leaning over the idling engine, checking the throttle linkage, my long scarf got tangled in the alternator belt, which yanked my head down towards the spinning alternator pulley. I avoided an Isadora Duncan–like fate when the scarf stalled out the engine with my face an inch from getting ripped to shreds by the pulley. It was if the Manx knew I was thinking about selling it.

As it rolled down the street on the back of my friend’s trailer, I felt no wistful stirrings, no seller’s remorse about the end of my Manx madness. But I do now. Despite the Manx’s multiple maladies, I loved driving it with the top peeled off—being seen in the crazy gold metalflake contraption with the brapp-brapp exhaust note that I had assembled myself.

It didn’t occur to me back then that by building it and fixing everything that broke I had enrolled in a two-year course in basic automotive engineering. Or that with each failure and subsequent repair, I was adding to the patchwork quilt of my automotive knowledge. That knowledge became the foundation of everything I’ve done in my career.

We can’t know how today’s experience is preparing us for something to come in our lives, how what we might learn in the present will open a door in the future. I can see now that in attempting something so far beyond my capabilities I learned the value of having a goal and going after it, of persevering through challenges, of finding mentors, and of asking for help when I needed it. I guess you could say building a Manx helped me to grow up.

So, thank you, Bruce Meyers. I owe you and your funny little dune buggy a lot. I was just a kid who wanted a car. What I ended up with was an automotive education, a feeling of accomplishment, and a cache of happy memories. And the smarts to never lean over a running engine when wearing a scarf.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

[ad_2]

Source link